King James Bible: Political Influence and Missing Books

Every now and then, I like to dive into the history behind things we often take for granted. Recently, I found myself reading about the origins of the King James Bible—a book that has shaped English-speaking culture more than almost any other. It reminded me just how much of our language, literature, and even everyday phrases come from those early translations.

The First King James Bible

The King James Version (KJV) of the Bible, one of the most influential books in the English-speaking world, was first published in 1611, with scholars generally pointing to May 2, 1611 as the release date.

Commissioned by King James I of England in 1604, the translation was intended to provide a standardized English Bible for use in churches. The first edition, printed in London by Robert Barker, was a large folio Bible designed for church pulpits, not for personal reading.

By 1612, smaller editions were printed, which allowed more widespread access.

Why the King James Bible Matters

The KJV has had an enormous influence, including:

- Language and Literature: Helping to standardize the English language and inspiring writers for centuries.

- Religion: Becoming the most widely read Bible in English, shaping Protestant thought and worship.

- Culture: Its phrasing and style have become deeply embedded in English-speaking culture.

It is estimated that over a billion copies of the King James Bible have been published worldwide.

The Roots of the KJV: Tyndale, the Great Bible, and the Apocrypha

The King James Bible didn’t appear out of nowhere. It was built on a foundation that began almost a century earlier:

William Tyndale (1494–1536)

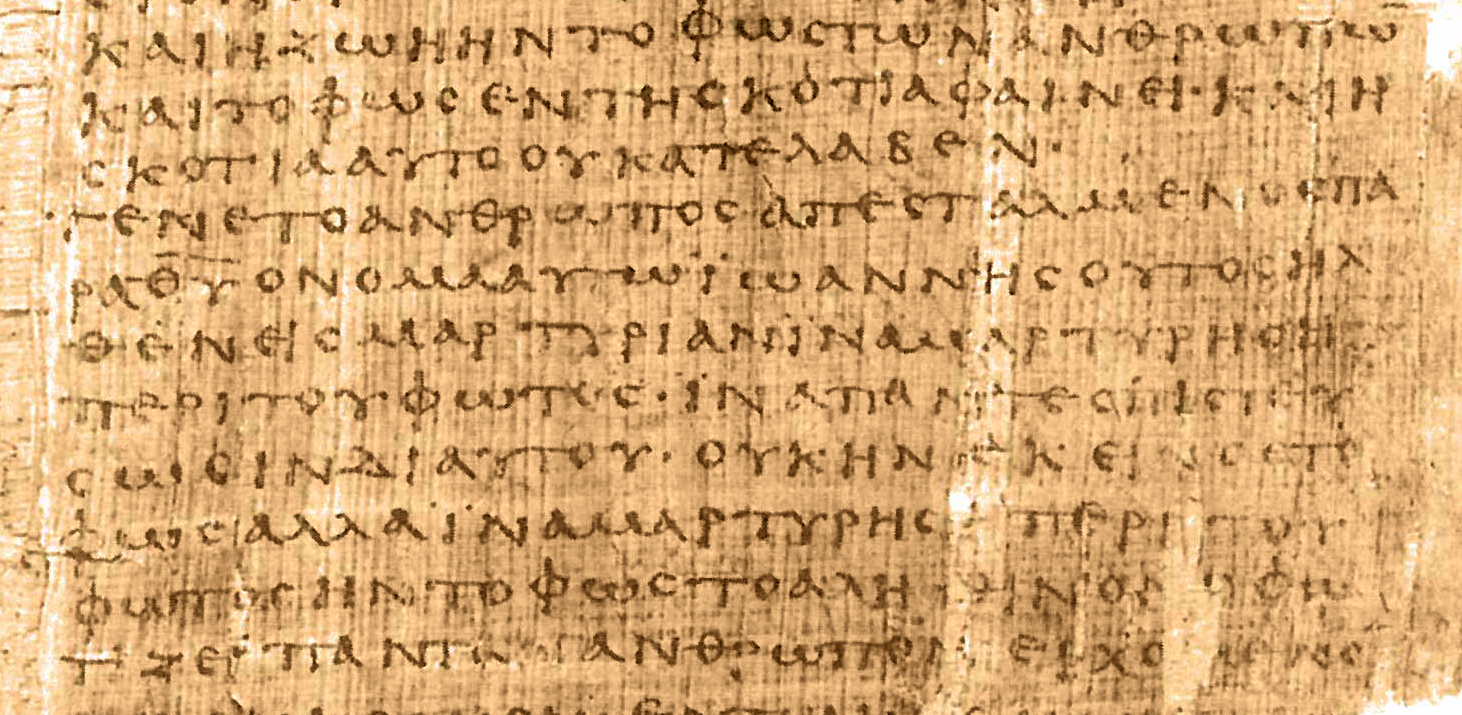

Tyndale was the first to translate the Bible into English directly from Hebrew and Greek. By 1526, he had printed an English New Testament and smuggled it into England. He was executed in 1536, but his words lived on—83% of the KJV New Testament uses his wording.The Great Bible (1539)

After Tyndale’s death, King Henry VIII authorized the Great Bible, compiled by Miles Coverdale, who leaned heavily on Tyndale’s work. This was the first Bible officially authorized for church use in England.The Apocrypha

The original 1611 KJV included the Apocrypha, a set of books found in the Septuagint (Greek Old Testament). These books (like Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, and 1 & 2 Maccabees) were printed between the Old and New Testaments.Over time, especially after the British and Foreign Bible Society decided in 1826 not to fund Bibles containing the Apocrypha¹, most Protestant editions dropped these books altogether. Catholic and Orthodox traditions, however, continue to include them.

King James’ Commission (1604)

In 1604, King James I convened the Hampton Court Conference and ordered a new translation that would unify the church. Forty-seven scholars worked for seven years, consulting original Hebrew and Greek manuscripts as well as earlier English translations.

The result was the 1611 King James Bible—a culmination of decades of scholarship and the vision of making scripture accessible in English.

William Tyndale: The Unsung Hero Behind the KJV

Tyndale was the first to translate the Bible into English directly from Hebrew and Greek, at a time when English translations were forbidden in England. Determined that “every ploughboy” should be able to read the Scriptures, he fled to Europe, printing copies of his New Testament and smuggling them into England.

In 1535, Tyndale was betrayed, arrested, and convicted of heresy. On October 6, 1536, he was strangled and burned at the stake. His last prayer was:

“Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”

Within months, King Henry VIII allowed a Bible in English.

Even though Tyndale did not live to see it, about 83% of the King James Bible is based on his translation work. His bold vision laid the foundation for English Bibles and influenced the English language itself.

The Books That Didn’t Make It

The King James Bible, like most Western Christian Bibles, does not include all the ancient texts that circulated in early Christianity and Judaism. Over time, decisions were made about which books were considered “canon” and which were left out.

Here are a few examples:

- The Book of Enoch: A Jewish text full of visions and prophecies, quoted in the New Testament (Jude 1:14), but left out of most Bibles. It is still part of the Ethiopian Orthodox Bible.

- The Gospel of Thomas: A collection of sayings attributed to Jesus, discovered in Egypt in 1945 as part of the Nag Hammadi library. It’s non-canonical but widely studied.

- Other texts in the Ethiopian Bible: The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church’s Bible contains 81 books, including works like Jubilees, 1 Enoch, and additional historical writings not found in the 66-book Protestant Bible.

The number of excluded or “lost” books varies depending on tradition, but these writings show how complex the history of scripture really is. It also reminds us not to take the version of history that one person tells us at face value. Instead, study widely, use discernment, and see what resonates with your own inner truth.

And honestly, it makes me wonder how much political influence and power struggles shaped which books were chosen, and which narratives were emphasized or suppressed. History shows us that religion and politics were deeply intertwined—and that influence is probably reflected in the Bibles we read today.

Quick Timeline: English Bible History

Key Milestones

- 1526: William Tyndale publishes the New Testament in English (printed abroad, smuggled into England).

- 1536: Tyndale is executed.

- 1539: The Great Bible is published—first officially authorized English Bible.

- 1604: King James I commissions a new translation.

- 1611: The King James Version is published, including the Apocrypha.

- Later: Protestant editions begin to omit the Apocrypha.

Why the KJV Became Dominant

- Royal authority: Officially commissioned by King James I.

- Standardization: Unified English-speaking churches under one Bible.

- Majestic language: Poetic, memorable style.

- Perfect timing: Printing press + rising literacy.

- Cultural reinforcement: Quoted in schools, sermons, and literature for centuries.

These factors combined to make the King James Bible the foundation for English-speaking Christianity.

Enter the New King James Version (NKJV)

Over 370 years after the original KJV was published, scholars and publishers recognized the need for a fresh approach. The New King James Version (NKJV) was commissioned in 1975 and published in 1982.

Its purpose was to:

- Update archaic language and grammar.

- Preserve the poetic style and cadence of the original KJV.

- Incorporate more accurate manuscript evidence available in the 20th century.

The NKJV became a bridge between tradition and modern English, offering a familiar tone with improved readability.

Conclusion

From Tyndale’s smuggled pages to the grand folio Bibles of 1611, the story of the King James Bible is one of courage, scholarship, and enduring impact.

Personally, I find it fascinating that this single book has shaped language, literature, and culture for over 400 years—and yet, there’s an entire library of other texts that almost made it in. It makes me wonder what future generations will consider “canonical” when they look back at us.

So why did the KJV, above all others, set the stage for English-speaking Christianity?

- It had royal backing (authorized by a king).

- It standardized worship by unifying competing English Bibles.

- It used a majestic and memorable language style.

- It arrived at the perfect moment in history, when printing and literacy were spreading.

- And over time, it became deeply woven into sermons, literature, and education, reinforcing its position as the English Bible.

¹ In 1826, the British and Foreign Bible Society made a formal policy change to stop including the Apocrypha in its funded publications. This decision influenced nearly all later Protestant Bible printings, which began omitting these books by default.

It’s also worth remembering that every translation—whether KJV, NKJV, or modern versions—is just that: a translation. Despite the incredible scholarship involved, there will always be questions about how close any translation comes to the meaning, nuance, and culture of the original Hebrew and Greek manuscripts. This is why comparing translations, studying the history, and using discernment remain so important.

References:

Dunham Bible Museum – English Bible History